- Copy to clipboard

- Thread starter

- #796

Saif

Senior Member

- Messages

- 14,475

- Reaction score

- 7,588

- Origin

- Residence

- Axis Group

Can Bangladesh afford servicing its debts?

The burden of public debt in Bangladesh is rising, both in absolute terms and relative to the size of the economy. By the end of the 2025-26 fiscal year, the government's total domestic and external debt is expected to reach Tk 23.42 trillion and it could go beyond Tk 28.93 trillion by 2027-28. Thi

Can Bangladesh afford servicing its debts?

SYED MUHAMMED SHOWAIB

Published :

Jul 18, 2025 23:29

Updated :

Jul 18, 2025 23:29

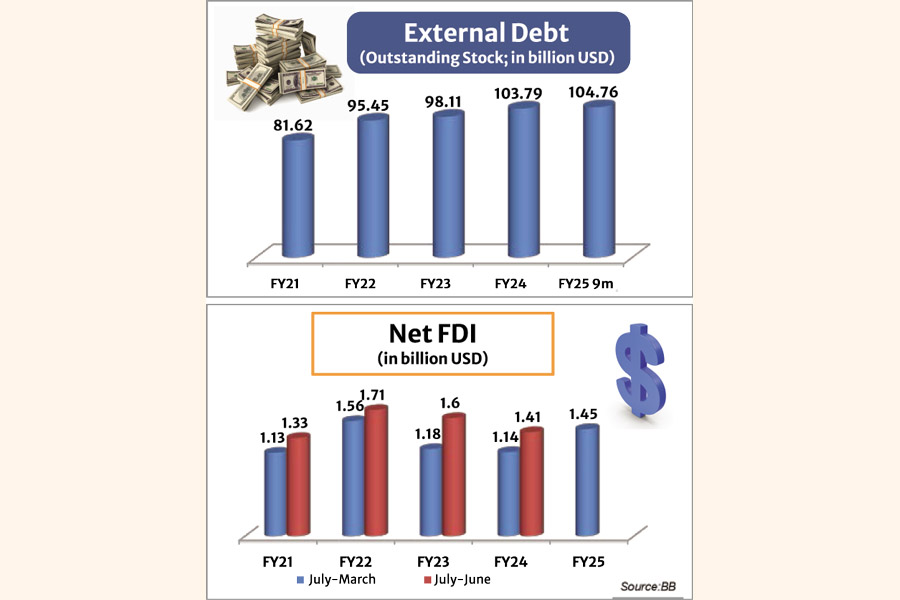

The burden of public debt in Bangladesh is rising, both in absolute terms and relative to the size of the economy. By the end of the 2025-26 fiscal year, the government's total domestic and external debt is expected to reach Tk 23.42 trillion and it could go beyond Tk 28.93 trillion by 2027-28. This mounting debt is one of the most serious challenges inherited by the interim government from its predecessor. When the previous Awami League government left office in August 2024, it had Tk 18.36 trillion in public debt accumulated through reckless borrowing in the name of development. The responsibility for repaying principals of these loans and servicing the interest now rests squarely on the current government. This unchecked accumulation of debt is creating intense economic pressure which could easily escalate into a full-blown crisis unless public finances are managed with utmost caution.

One of the most commonly used indicators in discussions of government debt is the debt-to-GDP ratio. Many consider the IMF's threshold for this ratio as a definitive benchmark for determining when debt crosses the danger line. For Bangladesh, the debt-to-GDP ratio stood at 37.62 per cent in the 2023-24 fiscal year, later revised down to 37.41 per cent in the latest budget. Projections suggest this ratio will gradually rise, reaching 37.72 per cent by the 2027-28 fiscal year. According to the IMF's fiscal monitoring report, a debt-to-GDP ratio of 55 per cent or higher would raise concerns for Bangladesh, meaning the current level does not immediately set off alarm bells. However, the upward trend warrants close attention. Ideally, if Bangladesh's borrowing had been subject to rigorous scrutiny and directed towards productive investments that boosted GDP growth, the rising debt would not have been seen as harmful. Unfortunately, much of the external borrowing over the past 15 years occurred without adequate scrutiny or negotiation, making the debt burden more severe than it needed to be. Moreover, many of the large-scale infrastructure projects financed by these loans were plagued by corruption. This often took the form of inflated costs, with unnecessary components added to justify budget escalations. Groups with vested interests reportedly exploited these loan-based mega projects by inflating costs multiple times. As a result, the country is now facing mounting pressure to pay back both interest and principal on a debt that it can no longer manage easily.

In theory, there is nothing inherently wrong about a country carrying debt. If the borrowed funds generate returns that exceed the cost of borrowing, such debt can be considered productive and sustainable. This is, in fact, a common feature of modern economies. But in practice, what happened in Bangladesh is that a growing share of public borrowing had gone towards covering routine expenses, propping up loss-making state-owned enterprises and subsidising sectors without credible reform plans. Entities such as the Bangladesh Power Development Board (BPDB), Bangladesh Petroleum Corporation (BPC) and Bangladesh Jute Mills Corporation (BJMC) continue to receive fiscal support despite persistent inefficiencies and structural weaknesses. Even within the ambit of the Annual Development Programme, capital spending is often hampered by poor project selection and implementation delays. Such uses of borrowed funds produce limited long-term economic returns, making the debt less justifiable and harder to service over time.

The ratio of interest paid to revenue is another critical indicator for assessing whether a nation's debt is becoming unmanageable. This matters because the cost of debt is closely tied to interest rates, and as those rates rise, the difficulty of servicing debt increases. Not all countries generate revenue at the same rate relative to GDP, nor do they borrow at the same cost. Countries that can borrow cheaply have more room to manage higher debt levels than those facing higher borrowing costs. Unlike advanced economies, Bangladesh cannot raise taxes or borrow at low interest rates with the same ease. In the fiscal year 2025-26, a staggering Tk 1.13 trillion has been allocated just for interest payments. This alone accounts for nearly one-seventh of the entire national budget. These interest expenses are expected to rise further in the coming years, placing increasing pressure on public finances. Bangladesh's upcoming graduation from the United Nations' Least Developed Country (LDC) status in 2026 will only add to this challenge. Once the country transitions out of the LDC category, it will no longer qualify for concessional financing which typically features low interest rates and long repayment periods. As a result, future borrowing will take place on more commercial terms, involving higher interest rates and shorter maturities. Consequently, debt servicing would consume growing portions of both foreign exchange reserves and fiscal revenues.

Had the country achieved stronger domestic revenue mobilisation in line with its expenditures, the debt burden would not have escalated to its current level. However, the National Board of Revenue (NBR) has consistently fallen short of its tax collection targets year after year, forcing the government to increasingly depend on borrowing, even to cover routine expenditures.

The government's own Medium-Term Debt Management Strategy reportedly acknowledges that Bangladesh has moved from a "low" to a "nearly high" risk category due to the growing volume of public debt. Notably, the country's external debt-to-export ratio has now reached 140 per cent, a level that the Finance Division itself considers alarming. This indicates that Bangladesh is earning significantly less from exports than it owes in foreign currency. If this trend persists, any combination of global events, be it a rise in oil prices, a slowdown in remittances or another pandemic, could trigger a balance of payments crisis.

All of this suggests that while Bangladesh may not currently face an imminent debt crisis, it has been heading in a risky direction for some time. The national budget for FY 2025-26 hints at a more cautious approach to spending, but greater discipline in project selection and debt management remains essential. Bangladesh still has the time and opportunity to place its public debt on a sustainable path, but that time is running out fast.

SYED MUHAMMED SHOWAIB

Published :

Jul 18, 2025 23:29

Updated :

Jul 18, 2025 23:29

The burden of public debt in Bangladesh is rising, both in absolute terms and relative to the size of the economy. By the end of the 2025-26 fiscal year, the government's total domestic and external debt is expected to reach Tk 23.42 trillion and it could go beyond Tk 28.93 trillion by 2027-28. This mounting debt is one of the most serious challenges inherited by the interim government from its predecessor. When the previous Awami League government left office in August 2024, it had Tk 18.36 trillion in public debt accumulated through reckless borrowing in the name of development. The responsibility for repaying principals of these loans and servicing the interest now rests squarely on the current government. This unchecked accumulation of debt is creating intense economic pressure which could easily escalate into a full-blown crisis unless public finances are managed with utmost caution.

One of the most commonly used indicators in discussions of government debt is the debt-to-GDP ratio. Many consider the IMF's threshold for this ratio as a definitive benchmark for determining when debt crosses the danger line. For Bangladesh, the debt-to-GDP ratio stood at 37.62 per cent in the 2023-24 fiscal year, later revised down to 37.41 per cent in the latest budget. Projections suggest this ratio will gradually rise, reaching 37.72 per cent by the 2027-28 fiscal year. According to the IMF's fiscal monitoring report, a debt-to-GDP ratio of 55 per cent or higher would raise concerns for Bangladesh, meaning the current level does not immediately set off alarm bells. However, the upward trend warrants close attention. Ideally, if Bangladesh's borrowing had been subject to rigorous scrutiny and directed towards productive investments that boosted GDP growth, the rising debt would not have been seen as harmful. Unfortunately, much of the external borrowing over the past 15 years occurred without adequate scrutiny or negotiation, making the debt burden more severe than it needed to be. Moreover, many of the large-scale infrastructure projects financed by these loans were plagued by corruption. This often took the form of inflated costs, with unnecessary components added to justify budget escalations. Groups with vested interests reportedly exploited these loan-based mega projects by inflating costs multiple times. As a result, the country is now facing mounting pressure to pay back both interest and principal on a debt that it can no longer manage easily.

In theory, there is nothing inherently wrong about a country carrying debt. If the borrowed funds generate returns that exceed the cost of borrowing, such debt can be considered productive and sustainable. This is, in fact, a common feature of modern economies. But in practice, what happened in Bangladesh is that a growing share of public borrowing had gone towards covering routine expenses, propping up loss-making state-owned enterprises and subsidising sectors without credible reform plans. Entities such as the Bangladesh Power Development Board (BPDB), Bangladesh Petroleum Corporation (BPC) and Bangladesh Jute Mills Corporation (BJMC) continue to receive fiscal support despite persistent inefficiencies and structural weaknesses. Even within the ambit of the Annual Development Programme, capital spending is often hampered by poor project selection and implementation delays. Such uses of borrowed funds produce limited long-term economic returns, making the debt less justifiable and harder to service over time.

The ratio of interest paid to revenue is another critical indicator for assessing whether a nation's debt is becoming unmanageable. This matters because the cost of debt is closely tied to interest rates, and as those rates rise, the difficulty of servicing debt increases. Not all countries generate revenue at the same rate relative to GDP, nor do they borrow at the same cost. Countries that can borrow cheaply have more room to manage higher debt levels than those facing higher borrowing costs. Unlike advanced economies, Bangladesh cannot raise taxes or borrow at low interest rates with the same ease. In the fiscal year 2025-26, a staggering Tk 1.13 trillion has been allocated just for interest payments. This alone accounts for nearly one-seventh of the entire national budget. These interest expenses are expected to rise further in the coming years, placing increasing pressure on public finances. Bangladesh's upcoming graduation from the United Nations' Least Developed Country (LDC) status in 2026 will only add to this challenge. Once the country transitions out of the LDC category, it will no longer qualify for concessional financing which typically features low interest rates and long repayment periods. As a result, future borrowing will take place on more commercial terms, involving higher interest rates and shorter maturities. Consequently, debt servicing would consume growing portions of both foreign exchange reserves and fiscal revenues.

Had the country achieved stronger domestic revenue mobilisation in line with its expenditures, the debt burden would not have escalated to its current level. However, the National Board of Revenue (NBR) has consistently fallen short of its tax collection targets year after year, forcing the government to increasingly depend on borrowing, even to cover routine expenditures.

The government's own Medium-Term Debt Management Strategy reportedly acknowledges that Bangladesh has moved from a "low" to a "nearly high" risk category due to the growing volume of public debt. Notably, the country's external debt-to-export ratio has now reached 140 per cent, a level that the Finance Division itself considers alarming. This indicates that Bangladesh is earning significantly less from exports than it owes in foreign currency. If this trend persists, any combination of global events, be it a rise in oil prices, a slowdown in remittances or another pandemic, could trigger a balance of payments crisis.

All of this suggests that while Bangladesh may not currently face an imminent debt crisis, it has been heading in a risky direction for some time. The national budget for FY 2025-26 hints at a more cautious approach to spending, but greater discipline in project selection and debt management remains essential. Bangladesh still has the time and opportunity to place its public debt on a sustainable path, but that time is running out fast.